I’m going to write for two hours every day. Preparing that garden bed will take me three hours. I’m just going to read for 20 minutes then go to sleep. This will be a quiet week. I have five full days free for garden work. Let me just look online for a few minutes to compare prices. I can write that letter this afternoon. I’m going to walk in the woods every day. And meditate. And get up early. And . . .

I’m going to write for two hours every day. Preparing that garden bed will take me three hours. I’m just going to read for 20 minutes then go to sleep. This will be a quiet week. I have five full days free for garden work. Let me just look online for a few minutes to compare prices. I can write that letter this afternoon. I’m going to walk in the woods every day. And meditate. And get up early. And . . .

I have a running list of expectations for myself. Some are big resolutions, and others are just little hopes for how the day is going to go. Looking at this list, it seems they have a lot to do with the idea of “managing time.” But I can’t really manage time. Or, at least, if I’m trying to manage time, I end up projecting myself into the future and critiquing my handling of the past, and I’m not really experiencing the present moment. I have recently learned that I walk around with a furrowed brow, looking angry (I’ve seen pictures!), without even knowing it. And all because I’ve set myself up by making expectations about how things are going to be, or how they should be, instead of just accepting how things are.

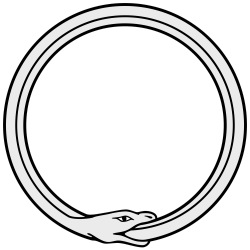

I am struggling a lot with this problem right now. Every new beginning offers a chance to make a change, whether it’s a big move, a brand new job, or just an annual New Year’s resolution or Lenten observance. I tend to put a whole bunch of great expectations on my plate all at once, and then--surprise!--I get stressed out. That doesn’t really help me in making the changes I seek. Instead, I turn inward, blaming myself, wondering why I can’t make good on my intentions. That starts a vicious cycle, because then I end up promising myself that I really will make good, that I really can keep my resolutions, that this plan for the day really should work . . . More promises, more good intentions, and more blaming and criticizing myself later.

Who’s with me on this? I want to grab a pitchfork and go marching right up to myself and say “Stop it! You’ve been trying this method for 40 years, and it doesn’t work!” This constant seeking to do better, do more, make a better plan--it’s all just so much stress. And as one of Anne’s friends once wisely remarked, “What good is stress? You can’t eat it.”

A friend recently lent me a thin volume by a Buddhist author, Cheri Huber, entitled There Is Nothing Wrong with You. It’s a great book. The basic idea is that in our society, we’ve been taught that we always need to better ourselves, and this has resulted in a constant stream of internal criticism and attempts at self-discipline. That negative barrage blocks out our deeper voice, our true impulses, which are inherently good--and if we could only get out of our own way, we would end up acting in ways that are caring to ourselves and others. I imagine there would be a giant, global sigh of relief if we all could surrender to the idea that, at heart, we are essentially good. That we didn’t have to try so hard to fix ourselves, to do better, all the time.

I have moments, from time to time, when I can shut off the flow of “shoulds” and just get in the flow of present-moment-life. When I do that, things are simply easier. The tasks get done, relations are warm, difficulties unwind themselves like a knot loosening and simply sliding apart, falling to the ground. And I wonder, “why did I think this was going to be so hard?” But most of the time I forget this wisdom, and sit there battering myself with unkind commands and judgements, as if straining and struggling and pushing harder will loosen the knot. (Pssst: it doesn’t.)

So here I am, another morning, looking out upon the rolling hills, and faced with a choice: I can be peaceful and grateful and accept the day as it comes, or I can berate myself for not getting up earlier, for having coffee instead of doing yoga, for all the things on my to-do list I thought I’d get done yesterday, or the day before... Giving up all those great expectations means letting go of so many things--the idea that I’m really in control of whatever happens (I’m not!), the belief that I need to always do more and better, the notion that life as it is, in this moment, isn’t already just fine. Engaging the present moment as it is means letting go of any expectation that it should be different. The great Zen poet Gertrude Stein* said it best, “It is what it is what it is.” And my long-time favorite Ani DiFranco has a lovely lyric about this very thing, in her song “As Is”:

When I look around, I think this, this is good enough.

And I try to laugh at whatever life brings.

‘Cause when I look down, I just miss all the good stuff.

And when I look up, I just trip over things.

*Just kidding.